Judge Executive speaks about the county’s responsibilities

Published 6:59 am Thursday, August 30, 2018

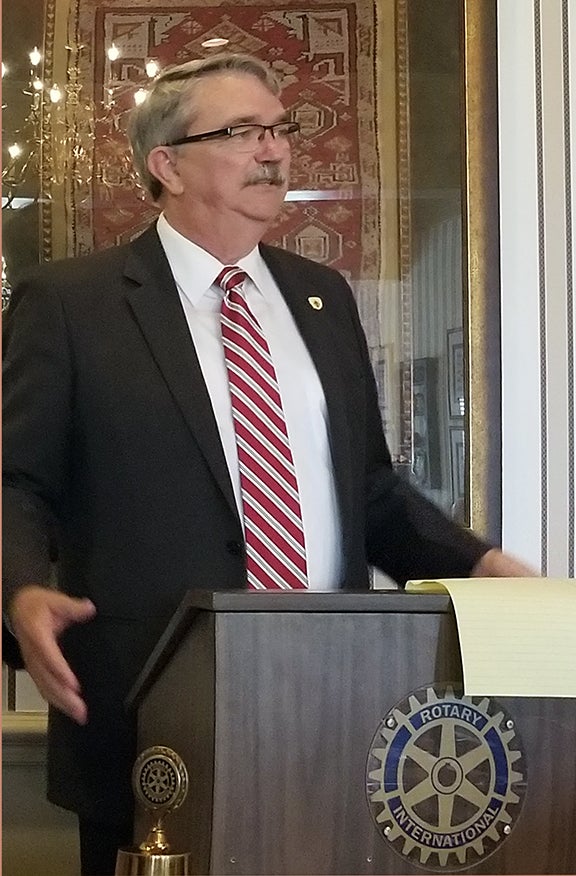

- Photo by Dave Fairchild Boyle County Judge-Executive Harold McKinney speaks to Danville Rotary Friday.

By DAVE FAIRCHILD

Danville Rotary

Boyle County Judge Executive Harold McKinney’s Aug. 24 presentation gave Rotarians an overview of the county’s services to the community. He feels that a lot of the people do not have a clear understanding of the division of responsibility between the county and the city.

Judge McKinney began his presentation with the Mercy Medical Services. The fiscal court funds, trains and equips that program. McKinney said that Public Works maintains the county’s 138 miles of roadways. He mentioned that the cost of salt has gone from around $60 a ton in 2017 to over a $100 a ton this year.

The next department McKinney addressed was solid waste. He spoke highly of Donna Fechter, director of Solid Waste and Recycling. “Donna, who is leaving us, has won ‘Solid Waste Director of the Year’ so many times they ruled her ineligible for any more titles!”

“We are blessed to enjoy the job performance we receive from our humane society. If you go there you won’t know who works for whom. That’s the way it should be.” The county works closely with the humane Society’s staff, but does not own the building or control the staff.

Some in the audience were surprised to learn that the county saves money by being self-insured. “We have our own private insurance company. We pay a premium and have a third-party administrator. Also surprising to some was that the county clerk is a free standing constitutional office. Its operating budget is fee based; the fiscal court does not fund the county clerk’s operation. In fact, the clerk’s office puts surplus fee collections into the fiscal court’s budget.

The sheriff’s office is also a freestanding constitutional agency with its own budget. The fiscal court supplements the sheriff’s budget to support a safer community through more policing. “You all know that drugs and all the related crimes and resultant costs are the biggest problem the county faces. Our jail is the biggest component in our budget.” Boyle County has a joint Jail with Mercer County. Boyle is the chief administrator and oversees its operation. The costs are split based on the ratio of inmates.

Judge McKinney said that the annual cost per jail bed is around $20,000 and construction costs to build a new jail runs $75-80,000 per bed. “There’s a lesson here folks, we don’t want to be building a jail anytime soon.” The county’s jail has 220 beds now. It has housed as many as 400 inmates. Currently, the population averages about 250. McKinney thinks that the capacity might be adequate with the addition of some treatment rooms. “What we need to be doing is providing help to rehabilitate those with addiction problems. It’s a lot cheaper than building new jails.”

McKinney mentioned that the recidivism of rehabilitated drug users is lower than the general population of inmates. He also pointed out that more women are being incarcerated for illegal drug use, which leads to unsupported children being placed in foster homes. He feels placing the mother in an outpatient program and letting her continue to care for her children is a much better approach.

McKinney believes EKU’s expanding pilot training program creates an opportunity for the Boyle County Airport to build a new terminal and service EKU’s planned purchase of a training aircraft. He also champions the in-process development of a statewide broadband internet network and the related completion of a county-wide cell-phone tower network. “We must get broadband and good cell-phone service and internet service to everybody in this community. The southwest quadrant of our county doesn’t have good cell phone service. In that region, Emergency responders cannot transmit EKG data to the hospital before the patient arrives. That’s just not acceptable.”

He characterized the Perryville Battlefield State Historic Site as “an unpolished jewel” that should be designated as a National Park. He closed by announcing that the county is suing selected distributors of opioids. “We learned through researching the distribution process that a community with a population of about 500 had received over 500,00 doses of opioids. The Fiscal Court decided to litigate because if the state sued, the settlement money would not be returned to the county.”