Opioids are getting a lot of attention, but meth is staging a dangerous comeback

Published 7:05 pm Tuesday, January 15, 2019

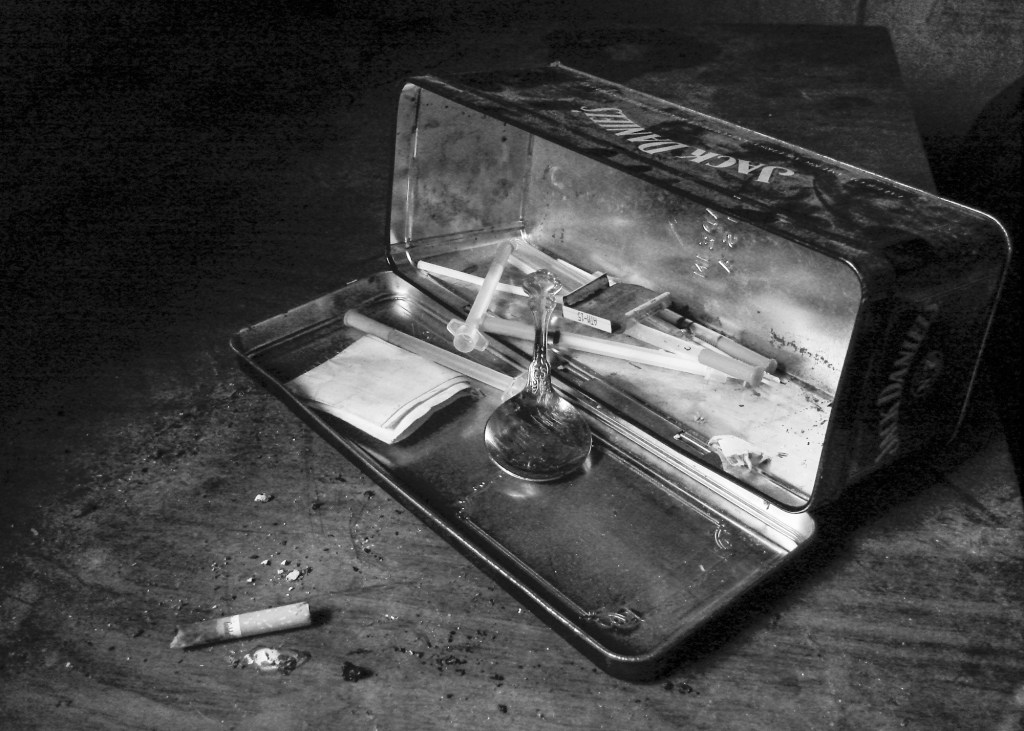

- Public domain

Editor’s note: This the second and final part of a series about the rising popularity of the illicit drug methamphetamine.

People who do meth are generally easier to identify than other types of drug users. Public Health Director Brent Blevins says the illicit stimulant seems to “devastate people … physically and mentally.”

“Their skin, teeth … They can’t sit still, they’re very jittery. And the sores all over, because they pick. They look really — strung out is the best way to say it, with their appearance.”

Trending

Meth is made with acetone, a substance usually used as nail polish remover or paint thinner. Other highly flammable or explosive ingredients, like anhydrous ammonia (fertilizers and clearers), lithium (found in batteries), red phosphorous (matchboxes and road flares) are also used. It contains corrosives, like hydrochloric acid (used to make plastic) that eats away at flesh; toluene, which is found in brake fluid; and sulfuric acid, found in drain cleaner. Other ingredients include ephedrine, found in cold medicines, which harms the respiratory system, nervous system and the heart with extended use; and sodium hydroxide, used to dissolve roadkill.

It’s an extremely toxic cocktail that plays havoc on the body.

“Both locally, statewide and nationally, meth is on the rise — again,” says Kathy Miles, coordinator of ASAP. She says what is actually being seen is the continuation of a lot of people using a mixture of drugs, depending on availability and cost. It’s been a real challenge, she says, for emergency medical personnel as far as treatment and detox.

“I would describe it as almost an excited delirium,” says Dr. Eric Guerrant about how patients act on meth. He’s director for emergency services at Ephraim McDowell Regional Medical Center.

“They’re out of control,” he says. It’s not uncommon for them to hit or bite staff in the ER.

The sores that develop from meth use are very telling, he says.

Trending

“It’s called delusional parasitosis — they think they’re infested with parasites or worms. That’s why they pick. They think they’re infested with something, and itch and scratch, creating those spots,” Guerrant says. The way meth interacts with the brain, he says, makes patients extremely irrational.

Many times, when “acutely intoxicated on meth,” Guerrant says law enforcement will have to assist ER staff with handling users safely. The only treatment is sedation and allowing the meth to wear off.

But after prolonged use, “You see deterioration of the mind, the body and soul, all together. The skin — they’ll lose massive amounts of weight and become emaciated, and unable to think clearly.” After a while, the chemical damage to the body and brain becomes difficult to completely recover from, even over time, Guerrant says.

Meth never really went away, he says.

Photo courtesy of Boyle County Sheriff’s Office

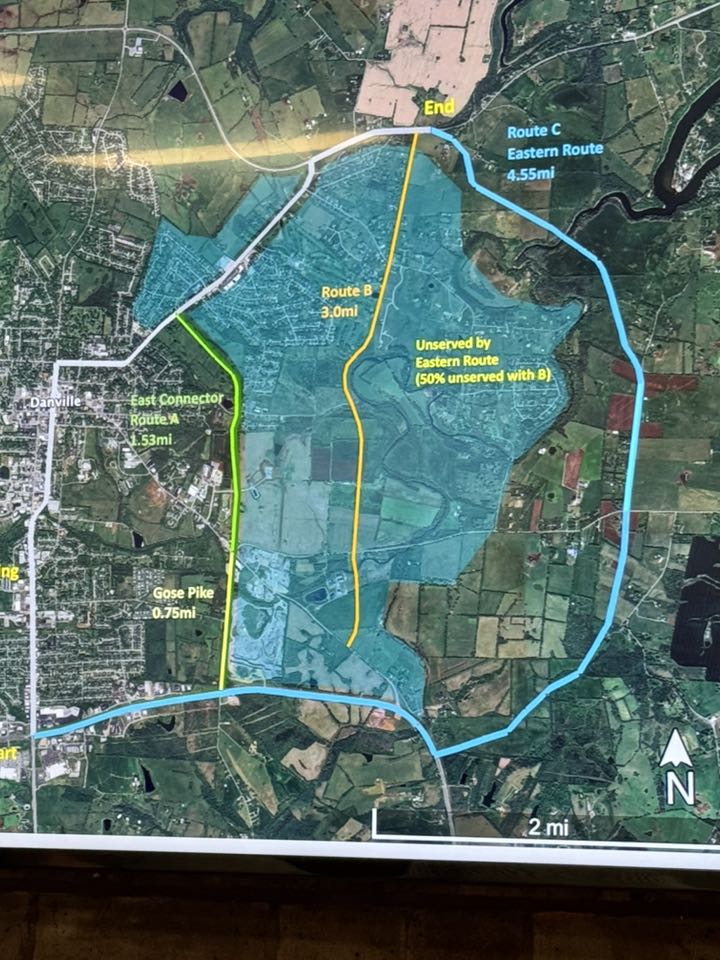

Sheriff Derek Robbins shared a picture from a recent, large crystal meth bust. The meth on the streets now is mostly “ice” — which is the purest form of methamphetamine, generally imported from Mexico or South America.

“The heroin epidemic got so much more press; there were higher incidents of sudden death. The methamphetamine addict by then has gotten to the end of their rope, burned all their bridges and gotten pushed to the edges of society.”

“I’d say a lot of the stuff we are finding now is methamphetamine, when it was heroin for a while,” says Boyle Sheriff Derek Robbins. It may be some dealers are too scared to deal in heroin anymore, he says. “But I know it seems to be turning towards crystal meth.”

In the past, meth in this area was homemade, created in a one-step lab, resulting in a powdery substance.

Jeremy Pingleton, 40, is a client undergoing treatment for meth addiction at Shepherd’s House. He started doing meth years ago, when it was called shake and bake, or bathtub crank. It was harder to get; back in those days, he says, you had to know someone who was cooking.

When he could no longer find it, he looked up the symptoms for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and went to the doctor. They prescribed him Adderall, a stimulant so closely watched now that patients must first take a urine test to show it’s in their system and they’re not selling it.

After his tolerance increased, he went back to the doctor and was prescribed Desoxyn — which is straight methamphetamine hydrochloride, a prescription that’s still on the market today. When he could no longer get prescriptions filled, he got ahold of crystal meth.

“My tolerance was so high, I just turned to shooting it,” he says. He lost weight and couldn’t keep a job down.

“Now, 99.9 percent of what we’re seeing is crystal. It’s more than likely coming from Mexico. It’s cheaper — where they’ve made it harder to get the ingredients to make it here, it’s cheaper to buy the more potent stuff that’s being imported,” Robbins says. And users are way harder to deal with, he says, because they’re unpredictable and don’t trust anyone due to paranoia.

Robbins says most of the meth busts locally have a tie to a supplier in a bigger city. Meth showing up in Danville is probably hitting four or five sets of hands before it gets here. It’s often coming from Chicago, Atlanta or St. Louis.

“The cartel is in control of that,” he says.

According to the Office of Drug Control Policy (ODCP), domestic production of meth has continued to decline. In 2011, it was at an all-time high, when 1,235 labs were reported. There were fewer than 100 reported in 2017. But meth produced in Mexico and South America has increased, and there were several large seizures of foreign produced meth in Kentucky in 2016 and 2017.

To put it in perspective, ODCP’s director, Van Ingram, says the homemade labs of the past were producing meth with about 40- to 50-percent purity.

“Ice (crystal meth) is over 90-percent pure. And being sold so cheaply, you can’t buy the ingredients and make it cheaper anymore,” Ingram says. “It’s flooding our streets right now.”

When meth was at its previous height, from 2007 to 2009, Ingram says they saw very little IV use. Smoking or snorting was the preferred method those days.

“Then we had a leveling off, and now it’s back — with a vengeance. And the pattern is injecting it, which even further exacerbates the problems with hepatitis and HIV,” Ingram says. “Which again makes the needle exchange programs so important.”

Another problem creeping up is meth with fentanyl added to it, Ingram says. Fentanyl is the powerful synthetic opioid responsible for many overdose deaths, because dealers add it to make their product more powerful than the next guy’s, he says.

“Bottom line, when you purchase illicit drugs you have no idea what you’re buying. We are seeing all these combinations, dealers experimenting with what users might like.”

Ingram says there are several ways those with addictions can get help. They can visit findhelpnowky.org; call (833) 859-4357; or text HOPE to 96714.