First MRT graduating class honored at Boyle jail

Published 1:00 pm Friday, August 21, 2020

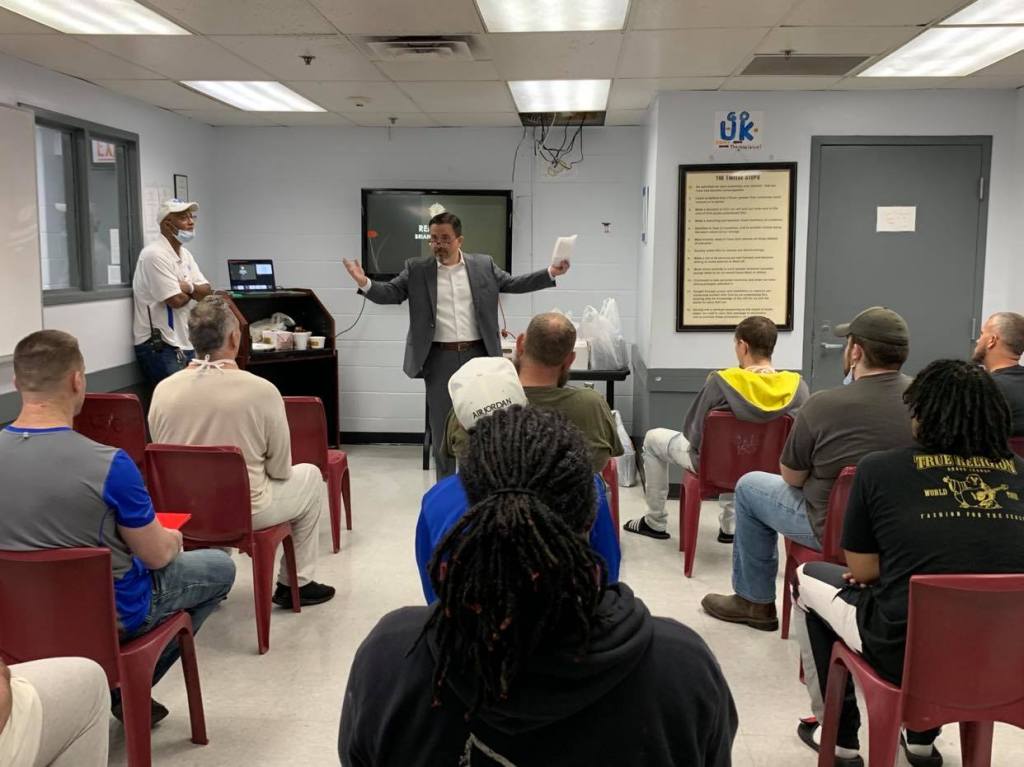

- Jailer Brian Wofford, right, and James Hunn, re-entry program director, speak to the MRT graduating class at Boyle County Detention Center. (Photo by Bobbie Curd)

Jailer, program leader say classes already affecting some inmates’ lives, helping them recognize underlying issues

On Friday night, several graduates stood up to be recognized as the first class to achieve a major step. But they weren’t wearing caps and gowns — they are all state inmates at Boyle County Detention Center, and had just finished the jail’s first-ever moral recognition therapy class, or MRT.

Although MRT has been around since the late 1980s — as one of the first cognitive-behavioral programs for offender populations — it was finally given the status of an “evidence-based program” by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration in 2008.

Jailer Brian Wofford said he “fought hard” to get the position of re-entry program director created, a title James Hunn holds since last year. Wofford said based on what he’s seen at the conclusion of the first class, it was worth fighting for.

Donning a suit for Friday’s occasion, Wofford said, “Of course I’m wearing a suit. I want these guys to understand that this is a big accomplishment for them. This is the first step in making those right choices, and we want them to continue the pattern.”

Hunn’s salary and MRT, along with the Portals New Direction program, are all paid for through the canteen fund. Wofford said the re-entry program was imperative to bring in, but he wanted to make certain it didn’t cost taxpayers any money.

With it being supported by canteen funds, which inmates and their families can pay into, Wofford said the program is something they are actually paying for themselves, and something they work hard at in order to achieve.

Trending

Creating trust

Portals, which is mandated by the Department of Corrections, is a 10-week class covering budgeting, life skills, credit, transportation and employment, for example, and is usually completed before MRT. Hunn said MRT is more of a “cognizance program.”

Hunn, who is back in school for his masters degree, said he decided to study criminal justice. “And that’s because I feel like they really need advocates.” He spoke about a note one inmate in the program left on his desk.

“It said ‘Thank you for believing there are some good people in jail.’ There are some good people in here who have just done bad things, like we all have,” Hunn said. “If society can just break down that stigma — I mean, that could be my son, your son. They’re all someone’s son. We need to have that vision to just … give people a chance.”

Hunn stood in the hallway outside the meeting room where inmates gathered, and became emotional when he spoke about how the men expressed vulnerabilities during classes, something many of them have never done before.

“It dives deep down into their behavior, challenges them to look at damaged relationships and accept responsibility,” he said. Through this process, he’s been amazed that this was the very first time for some of them to talk openly about extremely traumatic incidents they’ve endured.

Although the hand you’re dealt in life isn’t an excuse for criminal behavior, Hunn said it’s important they realize what their underlying issues are that contributed to getting jail time.

“It challenges them to face it all and begin to deal with it … talk in a group of other men who they grow to trust. That trust — that’s been very positive, and I’m so proud of them. They’ve impacted our lives, too,” Hunn said. “We talk a lot of times about prison or jail mentality, they don’t want to show their vulnerability because of the guys around them. They’ve said they’ve learned to trust each other, something that doesn’t happen a lot in these environments.”

Working through hopelessness

“For me, being in jail, you withhold a lot of things, you don’t want to open up,” said Channing Roberts, who’s been in for two years on drug-related charges and being caught with a gun. He stood in the hallway with fellow graduate Michael Hopkins, who is serving time for theft.

They both proudly held up their certificates of completion, and spoke about how much they learned through sessions with Hunn, someone they’ve grown to deeply respect and trust.

Roberts, originally of Richmond, had been on heroin for six years and had gone through treatment programs before. “But this really had me digging deep. It makes you be honest with yourself and about the damage you’ve caused,” something he said had a “really magical effect” on him because he didn’t feel any judgement when he opened up. “It’s made me believe in myself again.”

Hopkins said he didn’t realize the program was going to be as extensive as it is. “It gets into your emotions, kind of breaks you down and makes you understand who you were, and who you can be.” The days when the men shared testimonials about their lives were really emotional, something he didn’t expect.

Roberts said, “Everybody’s got that common thing in here — we made bad choices and caused a lot of harm. And being open about that really helps you work through it.” Since he’s been in jail, his brother died of an overdose. “And I’ve lost six or seven friends since I’ve been in, all from the same stuff I was using. So I feel like it’s a blessing that I’m alive.”

“For me, I’ve never had any drug issues,” Hopkins said, who is in jail for the first time at 41 years old. He served 16 months in Casey County before being moved to Boyle.

Roberts was a lieutenant on the Lincoln County Fire Department for nine years, and was a 400-hour certified firefighter. He had custody of his 15-year old daughter and had a home, but got involved with “the wrong people,” and was charged with stealing a semi truck and trailer of farm gates, worth about $150,000.

“My sister is the assistant police chief in Lancaster, so I feel like I really let her down,” Roberts said. When going through the program, he came to terms with some issues he had from a difficult childhood, after some health problems forced him to leave school in the 10th grade.

Roberts said MRT made him realize what he’s caused and attempt to make amends, and that he really does have people who love and support him in his life — a fact he’d lost touch with due to years of drug abuse. “I do have relationships where people care about me, my family, who’s there to back me up and support me. All I have to do is work on fixing some things. And I don’t want to die anymore.”

Roberts and Hopkins both said that in jail, it’s easy to see the difference between the people who have outside support and the ones who don’t. And the program offered this.

“Hopelessness is only worked through by getting introduced to hope,” Roberts said, and he’s working on his plan for the future, like moving into a sober living facility when he’s released. He could go home to his mom, “but I know (sober living) is best for me. I need to continue to work the program.”

Williams plans on going back to operating heavy equipment for a job. “And when I get this felony expunged, I want to go back to firefighting.”

‘I should be where you are’

Jailer Wofford gave closing remarks after the men watched a video of a speaker on The Butterfly Effect. He wanted them to remember that all choices cause a rippling effect, that the choices they make are going to affect someone else, positively or negatively, for eternity.

“If you look at statistics, I should be in here with you all instead of being up here,” Wofford said, and the room became dead silent.

He told the men that his parents were teenagers when they had him. He lost his mom when he was 16 due to a car wreck, and then his dad died when he was in college.

“My dad battled drug addiction my entire life. This is why …” Wofford paused, his voice cracking a bit. “This is why these programs are so important to me … I grew up going to visit my dad in prison due to drug charges.”

Wofford said after his dad got out, he had planned to go back to college and get his degree. “But he had one relapse, and he died.”

Wofford told the inmates if they have kids, “love them more than you love yourself,” and asked all of them to be equipped with a life plan when they are released. “And congratulations. I’m very proud of all of you.”

Hunn shared artwork done by program graduate Jeffrey Jones, and a six-page essay written by fellow grad Craig Gaines, titled “What Happened? An Essay on Black America.” He said the skill and talent in the room was an inspiration.

“You all have potential, and it may take you somewhere that you never imagined,” Hunn said. “I just want to encourage you guys tonight to use the potential you have. Because you all have it.”